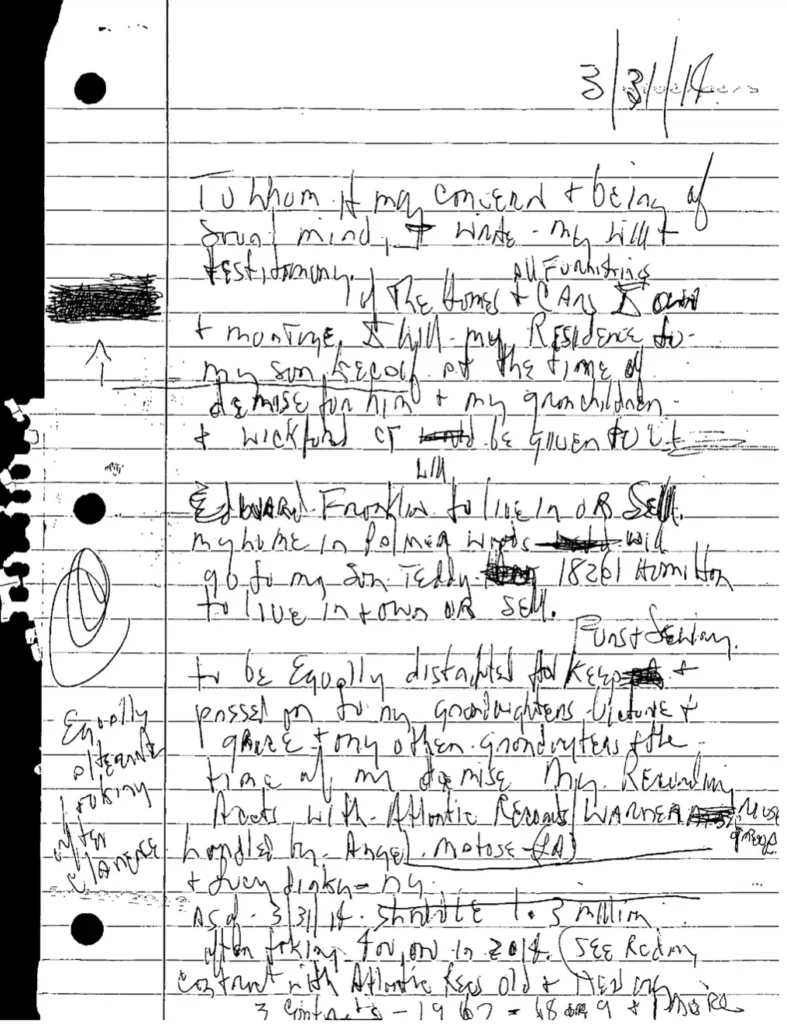

The family thought that singer Aretha Franklin had died in 2018 with no will. Then, months after her death a handwritten document was found in a notebook under a couch cushion. It seemed to be a holographic will.

Handwritten Will Governs Estate of Singer

Her family thought that she had died intesteste (without a will) meaning that her children would divide the estate equally. In fact, there were three wills, two from 2010 and one from 2014 that were written in her own hand, signed and legally. binding.

In fact, there were three will written out by Franklin without the aid of a lawyer. These handwritten, or holographic wills, are recognized in more than half of the states in the U.S., including New Jersey and Michigan, where Franklin lived when she died.

Perhaps it is fitting that the death of the singer who left who so left her mark on music and society in general, should be have a commensurately eventful passing. There was, as you may recall, the 10-hour funeral at a cost of $320,000 attended by multiple icons of music, sports and politics. Yet to come was the five-year will contest that ended in a two-day jury trial to decide which of her handwritten wills should be honored. (Four Pages Found in a Couch Are Ruled Aretha Franklin’s True Will)

New Jersey Law on Handwritten Wills

A will is generally speaking a formal document. New Jersey’s statutory law makes it easy to probate a will that has been executed using the formal process such that in most cases the document is self-proving and a judge is not involved.

Questions? Use our contact form or call to learn more on this issue.

The statute does, however, permit the probate, that is the official proving of a will, that does not follow the normal formalities and is hand written. The statute also allows for other documents to be accepted as wills that do not meet the normal formalities, but the process is more complicated.

Here is what the statute requires: that the will be in writing and is:

signed by the testator [the person disposing of property by will] or in the testator’s name by some other individual in the testator’s conscious presence and at the testator’s direction; and

signed by at least two individuals, each of whom signed within a reasonable time after each witnessed either the signing of the will as described in paragraph (2) or the testator’s acknowledgment of that signature or acknowledgment of the will. (N.J.S.A. 3B:3-2)

However, a will that is handwritten does not have to be formally witnessed in some circumstanes.

A will that does not comply with subsection a. is valid as a writing intended as a will, whether or not witnessed, if the signature and material portions of the document are in the testator’s handwriting.

The question of whether a document is intended by a will can require evidentiary proof. The statute permits proof that the testator intended the document as her or her will “by extrinsic evidence, including for writings intended as wills, portions of the document that are not in the testator’s handwriting.”

Documents Intended as Wills May be Proved in Court Proceeding

There are also times when a document was not executed with the formalities required by the statute and is not handwritten. A recent example was a will that was prepared, but after reviewing the document, the testator died before it was signed. (Trial Required in Suit to Admit Unsigned Will Over Charities Objections)

In the event that the person offering a document for probate that does not meet the statutory requirements, he or she can prove it was intended as a will by filing a complaint in the probate part of the Chancery Division of Superior Court. The statute provides that:

Although a document or writing added upon a document was not executed in compliance with N.J.S.3B:3-2, the document or writing is treated as if it had been executed in compliance with N.J.S.3B:3-2 if the proponent of the document or writing establishes by clear and convincing evidence that the decedent intended the document or writing to constitute: (1) the decedent’s will; (2) a partial or complete revocation of the will; (3) an addition to or an alteration of the will; or (4) a partial or complete revival of his formerly revoked will or of a formerly revoked portion of the will. (N.J.S.A. 3B:3-3)